Pubdate: Tue, 11 May 2010

Source: Huffington Post (US Web)

Copyright: 2010 HuffingtonPost com, Inc.

Author: Ethan Nadelmann

Note: Ethan Nadelmann is the executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance (www.drugpolicy.org)

Referenced: The 2010 National Drug Control Strategy http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/strategy/

Referenced: Wall Street Journal article http://www.mapinc.org/drugnews/v09/n514/a02.html

Bookmark: http://www.mapinc.org/people/Gil+Kerlikowske

ETHAN NADELMANN CRITIQUES OBAMA’S NEW DRUG WAR STRATEGY

The White House’s 2010 National Drug Control Strategy, released this morning by President Obama and drug czar Gil Kerlikowske, is both encouraging and discouraging. There’s no question that it points in a different direction and embraces specific policy options counter to those of the past thirty years. But it differs little on the fundamental issues of budget and drug policy paradigm, retaining the overwhelming emphasis on law enforcement and supply control strategies that doomed the policies of its predecessors.

First, to give credit where credit is due: The Obama administration has taken important steps to undo some of the damage of past administrations’ drug policies. The Justice Department has played an important role in trying to reduce the absurdly harsh, and racially discriminatory, crack/powder mandatory minimum drug laws; Congress is likely to approve a major reform this year. DOJ also changed course on medical marijuana, letting state governments know that federal authorities would defer to their efforts to legally regulate medical marijuana under state law. And they approved the repeal of the ban on federal funding of syringe exchange programs to reduce HIV/AIDS, thereby indicating that science would at last be allowed to trump politics and prejudice even in the domain of drug policy.

The new strategy goes further. It calls for reforming federal policies that prohibit people with criminal convictions and in recovery from accessing housing, employment, student loans and driver’s licenses. It also endorses a variety of harm reduction strategies ( even as it remains allergic to using the actual language of “harm reduction” ), endorsing specific initiatives to reduce fatal overdoses, better integration of drug treatment into ordinary medical care, and alternatives to incarceration for people struggling with addiction. All of this diverges from the drug policies of the Reagan, Clinton and two Bush administrations.

Director Kerlikowske told the Wall Street Journal last year that he doesn’t like to use the term “war on drugs” because “[w]e’re not at war with people in this country.” Yet 64% of their budget – virtually the same as under the Bush Administration and its predecessors – focuses on largely futile interdiction efforts as well as arresting, prosecuting and incarcerating extraordinary numbers of people. Only 36% is earmarked for demand reduction – and even that proportion is inflated because the ONDCP “budget” no longer includes costs such as the $2 billion expended annually to incarcerate people who violate federal drug laws.

There’s little doubt that this administration seriously wants to distance itself from the rhetoric of the drug war, but its new plan makes clear that it is still addicted to the reality of the drug war. Still missing is the full throttle commitment to treating drug misuse as a public health issue, and to harm reduction innovations that have proven so successful in Europe and Canada. Still present is the old rhetoric about marijuana’s great dangers and the need to keep current prohibitionist polices in place, with no mention of the fact or consequences of arresting roughly 750,000 people each year for possession of small amounts of marijuana.

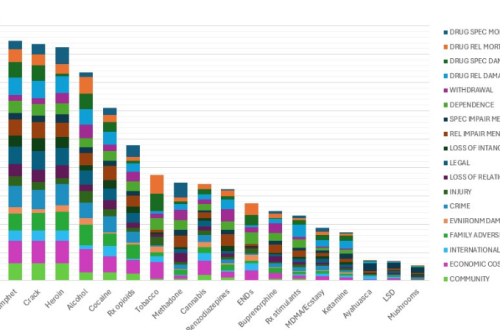

I had the pleasure of testifying a few weeks ago before the Congressional subcommittee charged with oversight of the drug czar’s office. The subcommittee chair, Dennis Kucinich, broke new ground on Capitol Hill by challenging the drug czar, whose testimony preceded mine, on his continuing commitment to supply control strategies notwithstanding their persistent failure, and on his resistance to embracing the language of harm reduction notwithstanding its growing acceptance by governments elsewhere. In my testimony, I asked the subcommittee to reform the ways that federal drug policy is evaluated by de-emphasizing the past emphasis on reducing drug use per se and focusing instead on reducing the death, disease, crime and suffering associated with both drug misuse and counter-productive drug policies.

So, yes, this administration is headed in a new direction on drug policy – but too slowly, too timidly, and with little vision of a fundamentally different way of dealing with drugs in the U.S. or global society. The strategy released today offers nothing that will reduce the prohibition-related violence in Mexico, Central America and Colombia, or seriously address the challenges in Afghanistan. It dares not take on the embarrassment of America’s record breaking and world leading rate of incarceration, especially of non-violent drug offenders. And it effectively acknowledges that politics will continue to trump science whenever the latter points toward politically controversial solutions.

We still have a long way to go.